Dr Michael Phillips is proud to be leading a research team with Dr Denise Chapman and Dr Jon Li exploring the use of Augmented Reality in one of Melbourne’s iconic public spaces: The Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG), Melbourne.

Dr Michael Phillips is proud to be leading a research team with Dr Denise Chapman and Dr Jon Li exploring the use of Augmented Reality in one of Melbourne’s iconic public spaces: The Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG), Melbourne.

Working with a team of four highly talented final year engineering students, Dr Phillips is leading this world first project which overlays video, audio, textual and animated information onto real world settings in the RBG. Viewed through a mobile device, this information addresses two of the cross curriculum priority areas in the Australian Curriculum: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures and Sustainability.

In addition to providing the 23,000 students who visit the RBG  annually, this application will soon be available free of charge for the 1,500,000 visitors who visit the gardens.

annually, this application will soon be available free of charge for the 1,500,000 visitors who visit the gardens.

While researching the affordances of technology in outdoor settings, Dr Phillips is also examining the socio-cultural processes of negotiation and the distribution of knowledge involved in making meaning of place.

To explore additional aspects of this project, please feel free to use the navigation menu below.

- About the project

- Augmented reality

- Learning outside the classroom

- Connections to the Australian Curriculum

- Project Images and Video Examples

- Recent media and invited presentations

Augmented reality is an emerging form of technology that superimposes information in various formats (for example, video, audio, 3 dimensional models, text) on to real world objects, for example in this project trees.

Using a mobile device such as a smart phone or tablet, visitors to the RBG will be able to access more information about the plants and spaces around them than they would be able to do using their eye sight alone. The video below explains some more about Augmented Reality.

Learning outside the classroom (LoTC) has long been a desired feature of many countries’ education systems and school curricula. The concept of school journeys introduced initially from Germany in the late nineteenth century greatly enlarged the range of contexts that children could experience first-hand (Cook, 2001) and was influential in shaping some of the learning experiences of secondary school students (Jenkins, 1980). More recently, the value of learning in different contexts has been highlighted by Australian based researchers who have reported benefits for student learning which occurs in museums (for example, see:Griffin, 2004), botanic gardens (Hofstein & Rosenfeld, 1996) as well as science and technology centres, museums, aquaria, and zoos (Rennie & McClafferty, 1995). The value of learning in these different contexts continues to be reflected in local curriculum such as the Victorian Essential Learning Standards (VELS) which requires students to:

gather information from both primary secondary sources. The most important primary source is information gathered from fieldwork studies. Fieldwork enables students to acquire knowledge by making first-hand observations, taking field measurements, mapping and recording phenomena in the real world in a variety of settings (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, 2005, p. 10).

While reinforcing the educational benefits of learning in environments outside the classroom, Dillon and Dickie (2012) also suggest that “contact with the natural environment affords a wide range of benefits, from educational to health and from cultural to social” (p.1). Pyle’s (2010) report to the Council for Learning outside the Classroom (CLoTC) in the United Kingdom indicated that teachers also benefited from the different pedagogical approaches afforded to them in LoTC experiences. While there is some consensus in the benefits for students and teachers when participating in LoTC whether in natural or built environments, there is increasing evidence that students and teachers are not participating in out-of-classroom learning experiences.

Scott, Boyd, Scott, and Colquhoun (2014) claim that, in spite of a growing academic focus on LoTC as pedagogy, “there has been concern that as a practice it is declining (Barker 2005; Reiss and Braund 2004; Tilling 2004), perhaps to the brink of extinction (Baker, Slingsby, and Tilling 2002 )” (p.1). International research has also confirmed that children are losing their connection with the natural environment and that children in urban environments are particularly disadvantaged with 10% of children playing in natural environments compared to 40% of adults doing so when they were young. This loss of connection with learning environments outside the classroom resulted in Louv (2005) coining the phrase Nature Deficit Disorder to describe the resultant lack of connection children have with outdoor environments. Such a dramatic ‘extinction of experience’ for nearly 4 million school students in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2014) can have “a detrimental long-term impact on environmental attitudes and behaviours” (Dillon & Dickie, 2012, p. 1) potentially influencing future societal trends and responses to critical issues such as climate change, reportedly the most significant long-term challenge facing the planet (Taylor, 2014).

While the potential value of LoTC has been established, less research has been conducted on the factors causing the decline in such experiences. While Scott et al. (2014) have synthesised literature identifying potential barriers to fieldwork linked to primary school teaching in Australia (and for international examples, see: Dillon et al., 2006; Rickinson et al., 2004), the research literature examining factors associated with the decline in LoTC in both natural and built environments is notably absent. This is particularly true of research examining LoTC in secondary school curricula, particularly in Australia, which is non-existent.

In their comprehensive review of outdoor learning research, Rickinson et al. (2004) found that “most research on outdoor learning looks exclusively at what happens out-of-doors” and “leaves unexplored all questions about how out-of-classroom learning can support within-the-classroom learning and vice versa” (p.57). Moreover, Rickinson et al. (2004) highlight “an urgent need for outdoor learning that takes a more integrated view of learning in different kinds of settings both within and beyond school” (p.57). Despite the identification of such a research imperative a decade ago, this shortcoming persists.

This study is designed to explore the connections between out-of-classroom and within-the-classroom learning “fuelled by a fundamental curiosity about things and processes – in this instance, emergent pedagogical elements and qualities – that we do not yet understand and that provoke us to think or imagine in new ways” (Ellsworth, 2005, p. 5). Specifically, this research will explore the relationship between within-the-classroom and out-of-classroom learning at two specific sites in metropolitan Melbourne – the Museums Victoria (MV) and Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG) – that have already given in principle agreements to participate in the project. These two institutions have been strategically chosen as research sites for this project as they not only both run educational programs but one site (MV) is largely indoors and ‘cultural’ in its focus, while the other site (RBG) is predominantly located outdoors and is primarily involved in education and curational aspects involving the natural environment.

On one level, this research is about the temporal (in)consistencies of student and teacher beliefs about learning in different physical contexts. To this end, this research aims to address the call for “research projects that look at the before, the during and the after” (Rickinson et al., 2004, p. 57) of out-of-classroom learning opportunities. On another level, this project aims to determine the extent to which teaching and learning needs to be understood in similar or different ways within variable physical and temporal contexts by questioning the purposes of out-of-classroom learning of itself and in relation to classroom learning.

In contrast to simply aligning LoTC experiences within curricular goals and objectives that often drive within-the-classroom pedagogies, this project aims to develop new knowledge by thinking experimentally about out-of-classroom pedagogies and their possible connections to within-the-classroom pedagogies in an attempt to take on what Rajchman (2000a) calls an “experimentalist relation to the future” (p.76). In contrast to predicting or programming the connections between these differing pedagogies, we are going to look at these anomalies as harbouring and expressing forces and processes of pedagogies “as yet unmade, that provoke us to think or imagine new [pedagogies] in new ways” (Rajchman, 2000b, p. 15).

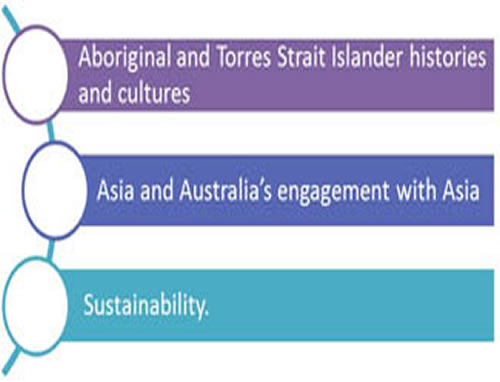

The Australian Curriculum contains both subject specific information for teachers, students and parents while also including three important cross curriculum priorities. This project addresses two of these cross curriculum priorities and the information below is taken from the Australian Curriculum website and explains more about this aspect of the Australian education system.

The Australian Curriculum has been written to equip young Australians with the skills, knowledge and understanding that will enable them to engage effectively with and prosper in a globalised world. Students will gain personal and social benefits, be better equipped to make sense of the world in which they live and make an important contribution to building the social, intellectual and creative capital of our nation.

Accordingly, the Australian Curriculum must be both relevant to the lives of students and address the contemporary issues they face. With these considerations and the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians in mind, the curriculum gives special attention to these three priorities:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures

- Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia

- Sustainability.

Cross-curriculum priorities are embedded in all learning areas. They will have a strong but varying presence depending on their relevance to the learning areas.

The content descriptions that support the knowledge, understanding and skills of the cross-curriculum priorities are tagged with icons. The tagging brings to the attention of teachers the need and opportunity to address the cross-curriculum priorities at this time. Elaborations will provide further advice on how this can be done, or teachers can click on the hyperlink which will provide further links to more detailed information on each priority.

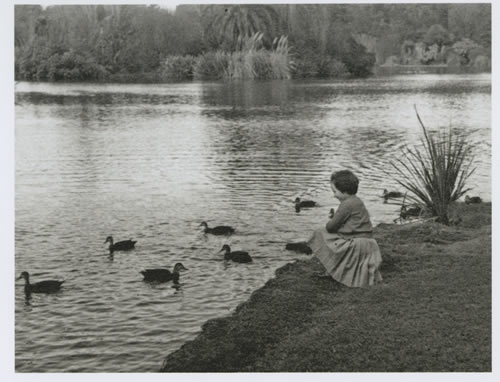

This project utilises a number of historical and contemporary images kindly supplied by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne. These images are used under licence and are not to be reproduced.

The combination of historical images and maps together with contemporary models, simulations, video and audio allows visitors to the RBG to access information in ways that, until now have not been possible.

Recent selected media appearances and invited presentations

- Phillips, M. (March, 2016) “Augmented reality and the future of Science Education”, World Science Festival.

- Phillips, M. (2015). Enhancing education by augmenting outdoor environments. e-technology. Technology in the classroom, 9 (October 2015), Australian Council for Educational Leaders, pp. 1-4.

- ABC Local Radio Melbourne (14 October 2015). Interview with Red Symons regarding Augmented Reality in the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne.

- Jacks, T. (23 August, 2015). Virtual reality: How Oculus Rift could change the way students learn. The Age, p.5.

- Ross, J. (15 April, 2015). Augmented Reality makes everyday life a classroom. The Australian, p.32

- Augmented reality and design thinking: Looking to the future. Alia College. 11 December 2014

- Through the looking glass and what you might find there: Augmented Reality and Education. Monash University Faculty of Education Teaching and Learning Seminar. 28 May 2014.